What Is the Art Term for Mary With Christs Body

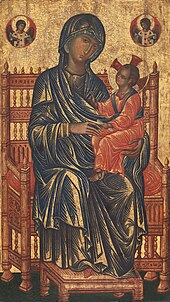

Our Female parent of Perpetual Help, Icon of the Virgin Mary, 16th century. St. Catherine'south Monastery in the Sinai.

The Salus Populi Romani icon, overpainted in the 13th century, merely going back to an underlying original dated to the 5th or sixth century.

A Madonna (Italian: [maˈdɔn.na]) is a representation of Mary, either lonely or with her child Jesus. These images are central icons for both the Catholic and Orthodox churches.[i] The word is from Italian ma donna 'my lady' (archaic). The Madonna and Kid blazon is very prevalent in Christian iconography, divided into many traditional subtypes especially in Eastern Orthodox iconography, oftentimes known afterward the location of a notable icon of the blazon, such as the Theotokos of Vladimir, Agiosoritissa, Blachernitissa, etc., or descriptive of the depicted posture, as in Hodegetria, Eleusa, etc.

The term Madonna in the sense of "picture or statue of the Virgin Mary" enters English usage in the 17th century, primarily in reference to works of the Italian Renaissance. In an Eastern Orthodox context, such images are typically known as Theotokos. "Madonna" may be generally used of representations of Mary, with or without the infant Jesus, is the focus and central effigy of the image, possibly flanked or surrounded past angels or saints. Other types of Marian imagery have a narrative context, depicting scenes from the Life of the Virgin, e.one thousand. the Announcement to Mary, are not typically called "Madonna".

The primeval depictions of Mary date to Early Christian art of the (2d to 3rd centuries, found in the Catacombs of Rome.[two] These are in a narrative context. The classical "Madonna" or "Theotokos" imagery develops from the 5th century, equally Marian devotion rose to great importance subsequently the Council of Ephesus formally affirmed her status every bit "Mother of God or Theotokos ("God-bearer") in 431.[3] The Theotokos iconography equally it developed in the 6th to eighth century rose to great importance in the high medieval catamenia (12th to 14th centuries) both in the Eastern Orthodox and in the Latin spheres.

Co-ordinate to a tradition first recorded in the 8th century, and still stiff in the Eastern Church building, the iconography of images of Mary goes back to a portrait drawn from life by Luke the Evangelist, with a number of icons (such as the Panagia Portaitissa) claimed to either represent this original icon or to be a straight copy of it. In the Western tradition, depictions of the Madonna were greatly diversified by Renaissance masters such every bit Duccio, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giovanni Bellini, Caravaggio, and Rubens (and further by certain modernists such as Salvador Dalí and Henry Moore), while Eastern Orthodox iconography adheres more closely to the inherited traditional types.

Terminology [edit]

Liturgy depicting Mary as powerful intercessor (such as the Akathist) was brought from Greek into Latin tradition in the 8th century. The Greek title of Δεσποινα (Despoina) was adopted as Latin Domina "Lady". The medieval Italian Ma Donna pronounced [maˈdɔnna] ("My Lady") reflects Mea Domina, while Nostra Domina (δεσποινίς ἡμῶν) was adopted in French, as Nostre Matriarch "Our Lady".[4]

These names signal both the increased importance of the cult of the virgin and the prominence of art in service to Marian devotion during the late medieval menstruum. During the 13th century, peculiarly,[ commendation needed ] with the increasing influence of knightly and aristocratic civilisation on poetry, song and the visual arts, the Madonna is represented as the queen of Heaven, often enthroned. Madonna was meant more to remind people of the theological concept which is placing such a high value on purity or virginity. This is also represented by the colour of her wearable. The color blue symbolized purity, virginity, and royalty.[ commendation needed ]

While the Italian term Madonna paralleled English Our Lady in late medieval Marian devotion, it was imported as an art historical term into English language usage in the 1640s, designating specifically the Marian art of the Italian Renaissance. In this sense, "a Madonna", or "a Madonna with Child" is used of specific works of fine art, historically mostly of Italian works. A "Madonna" may alternatively exist called "Virgin" or "Our Lady", only "Madonna" is not typically applied to eastern works; eastward.g. the Theotokos of Vladimir may in English be called "Our Lady of Vladimir", while it is less usual, but non unheard of, to refer to it as the "Madonna of Vladimir".[5]

Modes of representation [edit]

There are several distinct types of representation of the Madonna.

- One type of Madonna shows Mary alone (without the kid Jesus), and standing, more often than not glorified and with a gesture of prayer, benediction or prophesy. This blazon of image occurs in a number of ancient apsidal mosaics.

- Full-length standing images of the Madonna more frequently include the infant Jesus, who turns towards the viewer or raises his hand in benediction. The most famous Byzantine image, the Hodegetria was originally of this type, though nearly copies are at half-length. This blazon of prototype occurs frequently in sculpture and may be establish in fragile ivory carvings, in limestone on the central door posts of many cathedrals, and in polychrome wooden or plaster casts in nearly every Catholic Church. In that location are a number of famous paintings that draw the Madonna in this manner, notably the Sistine Madonna past Raphael.

- The "Madonna enthroned" is a blazon of image that dates from the Byzantine period and was used widely in Medieval and Renaissance times. These representations of the Madonna and Child frequently take the course of large altarpieces. They also occur every bit frescoes and apsidal mosaics. In Medieval examples the Madonna is often accompanied by angels who support the throne, or by rows of saints. In Renaissance painting, particularly High Renaissance painting, the saints may be grouped informally in a blazon of composition known as a Sacra conversazione.

- The Madonna of humility refers to portrayals in which the Madonna is sitting on the ground, or sitting upon a depression cushion. She may be holding the Child Jesus in her lap.[6] This style was a product of Franciscan piety,[7] [viii] and perhaps due to Simone Martini. It spread speedily through Italia and by 1375 examples began to appear in Spain, France and Germany. It was the most popular amidst the styles of the early Trecento creative menstruation.[ix]

- Half-length Madonnas are the form near frequently taken by painted icons of the Eastern Orthodox Church, where the discipline matter is highly formulated so that each painting expresses one particular attribute of the "Female parent of God". Half-length paintings of the Madonna and Child are also mutual in Italian Renaissance painting, particularly in Venice.

- The seated "Madonna and Child" is a style of epitome that became specially popular during the 15th century in Florence and was imitated elsewhere. These representations are commonly of a small size suitable for a small altar or domestic employ. They ordinarily show Mary property the babe Jesus in an informal and maternal manner. These paintings often include symbolic reference to the Passion of Christ.

- The "Adoring Madonna" is a type pop during the Renaissance. These images, ordinarily small and intended for personal devotion, evidence Mary kneeling in adoration of the Christ Child. Many such images were produced in glazed terracotta as well every bit pigment.

- The nursing Madonna refers to portrayals of the Madonna breastfeeding the infant Jesus.

- The iconography of the Woman of the Apocalypse is applied to marian portraiture in a variety of ways over time, depending on the interpretation of the relevant Biblical passage.[10]

History [edit]

Painting of the Madonna and Kid by an anonymous Italian, offset half of 19th century

The earliest representation of the Madonna and Child may exist the wall painting in the Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome, in which the seated Madonna suckles the Child, who turns his caput to gaze at the spectator.[xi]

The primeval consistent representations of Mother and Child were adult in the Eastern Empire, where despite an iconoclastic strain in civilisation that rejected physical representations as "idols", respect for venerated images was expressed in the repetition of a narrow range of highly conventionalized types, the repeated images familiar as icons (Greek "image"). On a visit to Constantinople in 536, Pope Agapetus was accused of being opposed to the veneration of the theotokos and to the portrayal of her image in churches.[12] Eastern examples show the Madonna enthroned, even wearing the closed Byzantine pearl-encrusted crown with pendants, with the Christ Child on her lap.[13]

In the West, hieratic Byzantine models were closely followed in the Early Eye Ages, but with the increased importance of the cult of the Virgin in the twelfth and 13th centuries a wide diverseness of types developed to satisfy a flood of more than intensely personal forms of piety. In the usual Gothic and Renaissance formulas the Virgin Mary sits with the Infant Jesus on her lap, or enfolded in her arms. In before representations the Virgin is enthroned, and the Child may exist fully aware, raising his mitt to offer approving. In a 15th-century Italian variation, a babe John the Baptist looks on. The socalled Madonna della seggiola shows both of them: the Virgin embraces the infant Jesus, near John the Baptist.

Belatedly Gothic sculptures of the Virgin and Child may prove a standing virgin with the kid in her artillery. Iconography varies betwixt public images and private images supplied on a smaller scale and meant for personal devotion in the chamber: the Virgin suckling the Child (such as the Madonna Litta) is an epitome largely bars to individual devotional icons.

Early images [edit]

![]()

There was a groovy expansion of the cult of Mary after the Council of Ephesus in 431, when her status equally Theotokos ("God-bearer") was confirmed; this had been a field of study of some controversy until and so, though mainly for reasons to do with arguments over the nature of Christ. In mosaics in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, dating from 432–440, just after the quango, she is not all the same shown with a halo, and she is also non shown in Birth scenes at this date, though she is included in the Adoration of the Magi.

By the next century the iconic delineation of the Virgin enthroned conveying the baby Christ was established, as in the instance from the just group of icons surviving from this period, at Saint Catherine's Monastery in Arab republic of egypt. This type of depiction, with subtly changing differences of emphasis, has remained the mainstay of depictions of Mary to the nowadays 24-hour interval. The image at Mount Sinai succeeds in combining 2 aspects of Mary described in the Magnificat, her humility and her exaltation above other humans, and has the Hand of God higher up, up to which the archangels wait. An early icon of the Virgin as queen is in the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere in Rome, datable to 705–707 by the kneeling figure of Pope John Vii, a notable promoter of the cult of the Virgin, to whom the infant Christ reaches his hand. This type was long confined to Rome. The roughly one-half-dozen varied icons of the Virgin and Kid in Rome from the 6th–8th century grade the majority of the representations surviving from this period; "isolated images of the Madonna and Kid ... are so mutual ... to the present day in Catholic and Orthodox tradition, that it is difficult to recover a sense of the novelty of such images in the early Centre Ages, at least in western Europe".[14]

At this period the iconography of the Nativity was taking the form, centred on Mary, that information technology has retained up to the present twenty-four hours in Eastern Orthodoxy, and on which Western depictions remained based until the High Middle Ages. Other narrative scenes for Byzantine cycles on the Life of the Virgin were beingness evolved, relying on apocyphal sources to fill up in her life before the Annunciation to Mary. By this fourth dimension the political and economical collapse of the Western Roman Empire meant that the Western, Latin, church was unable to compete in the development of such sophisticated iconography, and relied heavily on Byzantine developments.

The earliest surviving image in a Western illuminated manuscript of the Madonna and Child comes from the Book of Kells of nigh 800 [15] (there is a similar carved image on the lid of St Cuthbert'due south coffin of 698) and, though magnificently decorated in the style of Insular art, the drawing of the figures can only be described as rather crude compared to Byzantine work of the flow. This was in fact an unusual inclusion in a Gospel volume, and images of the Virgin were irksome to announced in large numbers in manuscript fine art until the book of hours was devised in the 13th century.

The Madonna of humility by Domenico di Bartolo, 1433, is considered ane of the virtually innovative devotional images from the early on Renaissance.[xvi]

Byzantine influence on the Westward [edit]

Very few early images of the Virgin Mary survive, though the depiction of the Madonna has roots in ancient pictorial and sculptural traditions that informed the earliest Christian communities throughout Europe, Northern Africa and the Center East. Of import to Italian tradition are Byzantine icons, particularly those created in Constantinople (Istanbul), the capital of the longest, indelible medieval civilisation whose icons participated in borough life and were celebrated for their miraculous properties. Byzantium (324–1453) saw itself every bit the true Rome, if Greek-speaking, Christian empire with colonies of Italians living amongst its citizens, participating in Crusades at the borders of its state, and ultimately, plundering its churches, palaces and monasteries of many of its treasures. Later in the Center Ages, the Cretan schoolhouse was the main source of icons for the West, and the artists there could adapt their mode to Western iconography when required.

While theft is one fashion that Byzantine images made their way West to Italy, the relationship between Byzantine icons and Italian images of the Madonna is far more rich and complicated. Byzantine art played a long, disquisitional function in Western Europe, particularly when Byzantine territories included parts of Eastern Europe, Greece and much of Italy itself. Byzantine manuscripts, ivories, golden, silver and luxurious textiles were distributed throughout the West. In Byzantium, Mary'southward usual title was the Theotokos or Female parent of God, rather than the Virgin Mary and information technology was believed that salvation was delivered to the faithful at the moment of God'due south incarnation. That theological concept takes pictorial form in the image of Mary belongings her babe son.

However, what is most relevant to the Byzantine heritage of the Madonna is twofold. First, the earliest surviving independent images of the Virgin Mary are establish in Rome, the middle of Christianity in the medieval West. One is a valued possession of Santa Maria in Trastevere, one of the many Roman churches dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Another, a splintered, repainted ghost of its erstwhile cocky, is venerated at the Pantheon, that great architectural wonder of the Aboriginal Roman Empire, that was rededicated to Mary as an expression of the Church building's triumph. Both evoke Byzantine tradition in terms of their medium, that is, the technique and materials of the paintings, in that they were originally painted in tempera (egg yolk and ground pigments) on wooden panels. In this respect, they share the Ancient Roman heritage of Byzantine icons. 2nd, they share iconography, or subject matter. Each epitome stresses the maternal role that Mary plays, representing her in human relationship to her baby son. It is difficult to gauge the dates of the cluster of these earlier images, however, they seem to exist primarily works of the 7th and eighth centuries.

Later medieval catamenia [edit]

It was not until the revival of monumental panel painting in Italia during the twelfth and 13th centuries, that the prototype of the Madonna gains prominence outside of Rome, especially throughout Tuscany. While members of the mendicant orders of the Franciscan and Dominican Orders are some of the first to committee panels representing this subject matter, such works quickly became popular in monasteries, parish churches, and homes. Some images of the Madonna were paid for past lay organizations chosen confraternities, who met to sing praises of the Virgin in chapels found within the newly reconstructed, spacious churches that were sometimes dedicated to her. Paying for such a piece of work might likewise be seen as a form of devotion. Its expense registers in the utilise of sparse sheets of existent gilded foliage in all parts of the panel that are non covered with paint, a visual analogue not only to the plush sheaths that medieval goldsmiths used to decorate altars, but also a means of surrounding the epitome of the Madonna with illumination from oil lamps and candles. Even more than precious is the vivid blue curtain colored with lapis lazuli, a stone imported from Afghanistan.

This is the case of ane of the most famous, innovative and awe-inspiring works that Duccio executed for the Laudesi at Santa Maria Novella in Florence. Often the calibration of the work indicates a great deal near its original role. Often referred to as the Rucellia Madonna (c. 1285), the console painting towers over the spectator, offering a visual focus for members of the Laudesi confraternity to gather before it as they sang praises to the image. Duccio made an even grander image of the Madonna enthroned for the high altar of the cathedral of Siena, his home town. Known equally the Maesta (1308–1311), the prototype represents the pair as the center of a densely populated court in the primal role of a complexly carpentered piece of work that lifts the court upon a predella (pedestal of altarpiece) of narrative scenes and standing figures of prophets and saints. In plow, a modestly scaled image of the Madonna every bit a one-half-length figure holding her son in a memorably intimate delineation, is to exist found in the National Gallery of London. This is clearly made for the individual devotion of a Christian wealthy plenty to hire one of the near important Italian artists of his twenty-four hour period.

The privileged possessor need non go to Church to say his prayers or plead for salvation; all he or she had to practise was open the shutters of the tabernacle in an act of individual revelation. Duccio and his contemporaries inherited early on pictorial conventions that were maintained, in part, to necktie their own works to the authority of tradition.

Despite all of the innovations of painters of the Madonna during the 13th and 14th centuries, Mary can normally exist recognized by virtue of her attire. Customarily when she is represented as a youthful mother of her newborn child, she wears a deeply saturated blue drapery over a carmine garment. This mantle typically covers her caput, where sometimes, ane might see a linen, or later, transparent silk veil. She holds the Christ Child, or Baby Jesus, who shares her halo as well equally her regal bearing. Ofttimes her gaze is directed out at the viewer, serving as an intercessor, or conduit for prayers that menses from the Christian, to her, and only and so, to her son. However, tardily medieval Italian artists as well followed the trends of Byzantine icon painting, developing their own methods of depicting the Madonna. Sometimes, the Madonna's circuitous bond with her tiny child takes the course of a close, intimate moment of tenderness steeped in sorrow where she merely has eyes for him.

While the focus of this entry currently stresses the delineation of the Madonna in panel painting, her image likewise appears in mural ornamentation, whether mosaics or fresco painting on the exteriors and interior of sacred buildings. She is constitute loftier above the alcove, or east terminate of the church building where the liturgy is celebrated in the West. She is as well found in sculpted class, whether minor ivories for private devotion, or large sculptural reliefs and free-continuing sculpture. As a participant in sacred drama, her prototype inspires one of the near of import fresco cycles in all of Italian painting: Giotto'southward narrative cycle in the Arena Chapel, adjacent to the Scrovegni family's palace in Padua. This program dates to the first decade of the 14th century.

Italian artists of the 15th century onward are indebted to traditions established in the 13th and 14th centuries in their representation of the Madonna.

Renaissance [edit]

While the 15th and 16th centuries were a time when Italian painters expanded their repertoire to include historical events, independent portraits and mythological subject matter, Christianity retained a stiff agree on their careers. Almost works of art from this era are sacred. While the range of religious subject affair included subjects from the One-time Testament and images of saints whose cults date after the codification of the Bible, the Madonna remained a ascendant bailiwick in the iconography of the Renaissance.

Some of the most eminent 16th-century Italian painters to turn to this subject were Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael,[note 1] Giorgione, Giovanni Bellini and Titian. They developed on the foundations of 15th-century Marian images by Fra Angelico, Fra Filippo Lippi, Mantegna and Piero della Francesca in item, among countless others. The discipline was equally popular in Early Netherlandish painting and that of the remainder of Northern Europe.

The subject retaining the greatest power on all of these men remained the maternal bond, even though other subjects, specially the Annunciation, and later the Immaculate Conception, led to a greater number of paintings that represented Mary solitary, without her son. Every bit a commemorative image, the Pietà became an important discipline, newly freed from its old role in narrative cycles, in function, an outgrowth of pop devotional statues in Northern Europe. Traditionally, Mary is depicted expressing compassion, grief and love, usually in highly charged, emotional works of art fifty-fifty though the most famous, early work by Michelangelo stifles signs of mourning. The tenderness an ordinary mother might feel towards her dearest kid is captured, evoking the moment when she kickoff held her infant son Christ. The spectator, after all, is meant to understand, to share in the despair of the mother who holds the body of her crucified son.

Modern images [edit]

In some European countries, such equally Federal republic of germany, Italian republic and Poland sculptures of the Madonna are constitute on the outside of city houses and buildings, or forth the roads in small enclosures.

In Germany, such a statue placed on the exterior of a building is called a Hausmadonna. Some date back to the Middle Ages, while some are still beingness made today. Usually plant on the level of the second floor or higher, and often on the corner of a business firm, such sculptures were plant in corking numbers in many cities; Mainz, for instance, was supposed to have had more than 200 of them before World State of war II.[19] The variety in such statues is every bit dandy equally in other Madonna images; ane finds Madonnas belongings grapes (in reference to the Song of Songs i:fourteen, translated as "My lover is to me a cluster of henna blossoms" in the NIV), "immaculate" Madonnas in pure, perfect white without child or accessories, and Madonnas with roses symbolizing her life determined by the mysteries of faith.[20]

In Italy, the roadside Madonna is a common sight both on the side of buildings and along roads in minor enclosures. These are expected to bring spiritual relief to people who pass them.[21] Some Madonnas statues are placed around Italian towns and villages every bit a thing of protection, or every bit a commemoration of a reported miracle.[22]

In the 1920s, the Daughters of the American Revolution placed statues chosen the Madonna of the Trail from coast to declension, marking the path of the old National Road and the Santa Fe Trail.[23]

Throughout his life, the painter Ray Martìn Abeyta created works inspired by the Cusco School style of Madonna painting, creating a hybrid of traditional and gimmicky Latino field of study thing representing the colonialist encounters between Europeans and Mesoamericans.[24] [25]

In 2015 iconographer Mark Dukes created the icon Our Lady of Ferguson, depicting the Madonna and child, in relation to the Shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri.[26]

Islamic view [edit]

The first important run across between Islam and the image of the Madonna is said to have happened during the Prophet Muhammad'southward conquest of Mecca. At the culmination of his mission, in 629 CE, Muhammad conquered Mecca with a Muslim army, with his commencement action existence the "cleansing" or "purifying" of the Kaaba, wherein he removed all the pre-Islamic pagan images and idols from inside the temple. According to reports collected by Ibn Ishaq and al-Azraqi, Muhammad did, however, protectively put his hand over a painting of Mary and Jesus, and a fresco of Abraham in gild to keep them from beingness effaced.[27] [28] In the words of the historian Barnaby Rogerson, "Muhammad raised his hand to protect an icon of the Virgin and Child and a painting of Abraham, just otherwise his companions cleared the interior of its clutter of votive treasures, cult implements, statuettes and hanging charms."[29]

The Islamic scholar Martin Lings narrated the event thus in his biography of the Prophet: "Christians sometimes came to exercise honour to the Sanctuary of Abraham, and they were made welcome like all the balance. Moreover one Christian had been allowed and even encouraged to paint an icon of the Virgin Mary and the child Christ on an inside wall of the Ka'bah, where information technology sharply contrasted with all the other paintings. Only Quraysh were more than or less insensitive to this dissimilarity: for them it was simply a question of increasing the multitude of idols by some other two; and it was partly their tolerance that fabricated them and so bulletproof.... Apart from the icon of the Virgin Mary and the child Jesus, and a painting of an onetime man, said to be Abraham, the walls inside had been covered with pictures of pagan deities. Placing his hand protectively over the icon, the Prophet told Uthman to come across that all the other paintings, except that of Abraham, were effaced."[xxx]

Notable types and individual works [edit]

In that location are a large number of articles on individual works of various sorts in Category:Virgin Mary in art and its sub-category. Run into also the incomplete List of depictions of the Virgin and Child. The term "Madonna" is often practical to representations of Mary that were not created by Italians. A small selection of examples include:

- Golden Madonna of Essen, the earliest large-scale sculptural example in Western Europe and a precedent for the polychrome wooden processional sculptures of Romanesque France, a type known as Throne of Wisdom.

- Madonna of humility depicting a Madonna sitting on the ground, or low cushions

- Madonna and Child, a painting by Duccio di Buoninsegna, from around the yr 1300.

- The Black Madonna of Częstochowa (Czarna Madonna or Matka Boska Częstochowska in Smooth) icon, which was, co-ordinate to legend, painted by St. Luke the Evangelist on a cypress table peak from the firm of the Holy Family.

- Madonna and Child with Flowers, possibly one of two works begun past Leonardo da Vinci.

- Madonna Eleusa (of tenderness) has been depicted both in the Eastern and Western churches.

- Madonna of the Steps, a relief by Michelangelo.

- Madonna della seggiola, by Raphael

- Madonna with the Long Neck, by Parmigianino.

- The Madonna of Port Lligat, the proper name of ii paintings by Salvador Dalí created in 1949 and 1950.

Paintings [edit]

- Madonna in Art

-

Madonna in Mandorla, Wolfgang Sauber, 12th century

-

Madonna and Angels, Duccio, 1282

-

Our Mother of Perpetual Help, probably an early Cretan piece of work, 13th or 14th century. A very popular Catholic prototype, which was certainly in Rome by 1499.

-

Mary and the child depicted equally a hodegetria. Tesselated icon in awe-inspiring style, early 13th century. Saint Catherine's Monastery in the Sinai, Egypt

-

Madonna in the rose-garden, by Stefan Lochner 1448

-

-

-

-

-

-

Statues [edit]

-

Egyptian ivory etching, one of the earliest examples of what in later on Byzantine times was chosen Eleousa, or "Virgin of Tenderness". 7th century.

-

-

-

-

A roadside Madonna in Ocieka, Poland.

-

A roadside Madonna alcove in Friuli, Italy.

-

-

Manuscripts and covers [edit]

See also [edit]

- Christian Art

- Art in Roman Catholicism

- Mary (mother of Jesus)

- Roman Catholic Marian art

- Pietà

- Nursing Madonna

- Life-giving Jump

- Eleusa icon

- Theotokos

- Icon of the Hodegetria

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- La Conquistadora

Notes [edit]

- ^ According to W. H. Wackenroder, some writings by Bramante reveal that Raphael told him that he discovered how to pigment his Madonnas in a visionary dream he had after praying to the Virgin.[18]

References [edit]

- ^ Doniger, Wendy, Merriam-Webster's encyclopedia of world religions, 1999, ISBN 0-87779-044-two p. 696.

- ^ Mary in Western Art by Timothy Verdon, Filippo Rossi 2005 ISBN 0-9712981-9-Ten p. 11

- ^ Shush, Raymond, Mariology: A Guide for Priests, Deacons, Seminarians, and Consecrated Persons 2008 ISBN i-57918-355-7[ page needed ]

- ^ Johannes Schneider, Virgo Ecclesia Facta, 2004, p. 74. Michael O'Carroll, Theotokos: A Theological Encyclopedia of the Blest Virgin Mary, 2000, p. 127.

- ^ "Madonna of Vladimir" e.yard. in Hans Belting, Edmund Jephcott; Edmund Jephcott (trans.) Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Era of Fine art, Academy of Chicago Press, 1996, p. 289.

- ^ Renaissance fine art: a topical lexicon by Irene Earls 1987 ISBN 0-313-24658-0 p. 174

- ^ A history of ideas and images in Italian art by James Hall 1983 ISBN 0-06-433317-5 p. 223

- ^ Iconography of Christian Fine art by Gertrud Schiller, 1971 ASIN B0023VMZMA p. 112

- ^ Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Expiry past Millard Meiss 1979 ISBN 0-691-00312-two pp. 132–133

- ^ Roten, Johann. "Crescent Moon: Meaning : University of Dayton, Ohio". udayton.edu.

- ^ Victor Lasareff, "Studies in the Iconography of the Virgin" The Art Message xx.one (March 1938, pp. 26–65 [pp. 27f]).

- ^ m. Mundell, "Monophysite church ornament" Iconoclasm (Birmingham) 1977, p. 72.

- ^ Every bit in the fresco fragments of the lower Basilica di San Clemente, Rome: run into John L. Osborne, "Early Medieval Painting in San Clemente, Rome: The Madonna and Child in the Niche" Gesta xx.2 (1981), pp. 299–310.

- ^ Nees, Lawrence. Early medieval fine art, 143–145, quote 144, Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-19-284243-ix, ISBN 978-0-xix-284243-v

- ^ Werner, Martin (1972). "The Madonna and Child Miniature in the Volume of Kells: Part I". The Art Bulletin. 54 (1): 1–23. doi:ten.2307/3048928. JSTOR 3048928.

- ^ Fine art and music in the early modern period by Franca Trinchieri Camiz, Katherine A. McIver ISBN 0-7546-0689-9 p. 15 [1]

- ^ National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

- ^ Salmi, Mario; Becherucci, Luisa; Marabottini, Alessandro; Tempesti, Anna Forlani; Marchini, Giuseppe; Becatti, Giovanni; Castagnoli, Ferdinando; Golzio, Vincenzo (1969). The Complete Piece of work of Raphael. New York: Reynal and Co., William Morrow and Company. p. 622.

- ^ Wöhrlin, Annette; Luzie Bratner; Marlene Höbel; Hiltraud Laubach; Anne-Madeleine Plum (2008). Mainzer Hausmadonnen. Ingelheim: Leinpfad. ISBN978-3-937782-70-half-dozen.

- ^ Anne-Madeleine Plum, "Kreuzzepter-Madonna--Zypertraube ind fruchtbringende Rede" and "Maria, Geheimnisvolle Rose", in Wöhrlin, Mainzer Hausmadonnen, pp. 49–54, 55–57.

- ^ Thomas Singer, 2004 The cultural complex ISBN i-58391-913-ix p. 68

- ^ Mark Pearson, 2006 Italy from a Backpack ISBN 0-9743552-4-0 p. 219

- ^ Madonna of the Trail

- ^ Williams, Stephen P. (August 5, 2007). "The Fine art Is Striking, and And then Are the Cars". The New York Times . Retrieved 9 Apr 2019.

- ^ Roberts, Kathaleen (June 29, 2014). "NM History Museum unveils rare colonial paintings of Mary". Albuquerque Periodical . Retrieved 9 Apr 2019.

- ^ http://nebraskaepiscopalian.org/?true cat=32&paged=ii

- ^ Guillaume, Alfred (1955). The Life of Muhammad. A translation of Ishaq's "Sirat Rasul Allah". Oxford Academy Press. p. 552. ISBN978-0196360331 . Retrieved 2011-12-08 .

Quraysh had put pictures in the Ka'ba including two of Jesus son of Mary and Mary (on both of whom be peace!). ... The apostle ordered that the pictures should be erased except those of Jesus and Mary.

- ^ Ellenbogen, Josh; Tugendhaft, Aaron (2011). Idol Anxiety. Stanford University Press. p. 47. ISBN978-0804781817.

When Muhammad ordered his men to cleanse the Kaaba of the statues and pictures displayed there, he spared the paintings of the Virgin and Child and of Abraham.

- ^ Rogerson, Barnaby (2003). The Prophet Muhammad: A Biography. Paulist Press. p. 190. ISBN978-1587680298.

- ^ Martin Lings, Muhammad: His Life Based on the Primeval Source (Rochester: Inner Traditions, 1987), pp. 17, 300.

External links [edit]

- Metropolitan Museum: The Virgin Mary in the Centre Ages

- The Madonna in Art at Project Gutenberg by Estelle M. Hurll (First printed 1897)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madonna_%28art%29